1. How AI can find the people most in need of COVID-19 aid

Why countries sometimes don't know which of their citizens to help, and how to fix it

Welcome to Giving to Strangers, my personal version of Vox’s Future Perfect.

Giving to Strangers is a newsletter for people who stare global problems in the face — climate change, animal welfare, global poverty — and believe that they require institutional, not just feel-good, solutions. Every week-ish, I share the ideas and people who are trying to make the world better, and offer a non-bogus thing that you can do to help.

Subscribe to the newsletter here!

I’ve been incredibly lucky in my three years post college to work for some absolute superstars of human beings. They’re often well established academics — Steve Levitt, author of Freakonomics, advisor to MI6 on catching terrorists, or Ted Miguel, whose study of deworming in Kenya nearly singlehandedly changed the health policy of an entire nation).

But it’s a totally different experience to see someone work who feels like a superstar in the making. I got this vibe from Josh Blumenstock two months ago, when I asked to join his project on targeting cash transfers. Blumenstock is a Professor at UC Berkeley, and just joined the Center for Effective Global Action as a co-Director. And I believe he’s doing some of the coolest work in response to Covid-19.

^ JB in the flesh (photo credit to the Center for Effective Global Action's post on his work)

The problem governments are facing during Covid-9

Like everybody else, economists are currently trying to do what they can to help whoever they can during COVID-19. And Blumenstock — whose training is in computer science and machine learning — is doing that by developing fancy AI algorithms to identify the poorest people & places in the world.

How does this help anybody during corona?

“People should not have to choose between death by Covid-19 or by hunger” — Faure E. Gnassingbé, President of Togo

COVID-19 and related lockdowns have tanked America’s economy, but they’re even worse for the hundreds of millions of people who live in extreme poverty. Whereas rich people have savings and robust social protection programs, people living in poverty are uniquely vulnerable to economic disruptions. For example, in a separate post, I wrote about how after the COVID-19 lockdown started, spending on food by families in Western Kenya dropped by almost half compared to what they could buy before COVID.

In response to the pandemic, most countries have launched some kind of emergency assistance. An economist at the World Bank, Ugo Gentilini, has been diligently keeping track of every. single. social protection policy that countries have launched in response to the coronavirus (a huge effort, may the Econ gods forever bless him, and may his papers make it to top 5 journals).

Ugo counted that cash transfers represent fully one-third of all COVID-related social protection programs around the world. But delivering cash is expensive, and there’s only so long that the governments can keep funding these programs. And when money becomes tight, that’s when it becomes really important to get it into the hands of people who could use it the most.

Why don’t countries know who their poorest citizens are?

Low-income countries often end up with little reliable information about who and where their citizens are, especially the poorest.

Lots of people in these countries are self-employed, or work on their farms, so they never file a W2 or equivalent. And if they do work, they work informally or just don’t pay taxes, so there’s no tax records. This means that government censuses and other databases are often out of date, and there’s definitely no way to go out and physically survey your whole country in the middle of a pandemic.

Josh’ two AI solutions to identify people living in poverty

Solution #1: Pictures from space

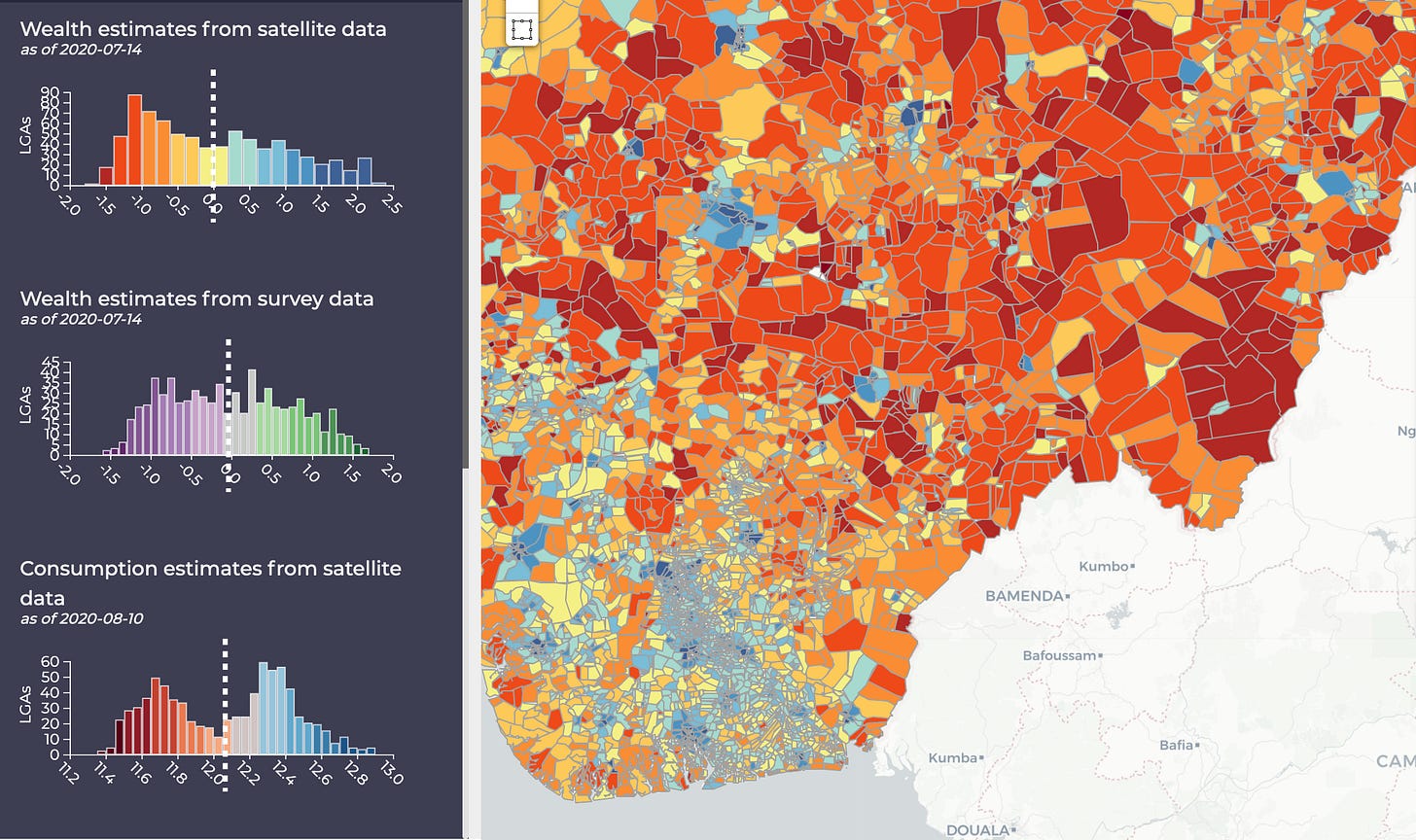

The first approach uses deep-learning algorithms to process satellite images. The satellite images show the quality of roofing on a house or the density of roads, which correlates well with actual economic conditions. Processing these satellite photos allows Blumenstock to generate detailed poverty maps, which can show a government the wealth of their country, even down to an individual neighborhood in a city.

^ a poverty map and dashboard showing very granular poverty rates, overlaid with coronavirus cases (in circles). How freaking cool?!

Solution #2: Phone records

Poor versus rich people use their phones differently: poorer people make shorter calls, have fewer contacts, and carry around less balance in their mobile money accounts. Blumenstock’s algorithms take data from mobile phone companies in several African countries, pick up on these patterns, and identify which users are rich vs poor.

Since April of 2020, Blumenstock’s team has been using these two approaches to help out several governments to identify which people they should prioritize for cash transfer programs.

Takeaway

Blumenstock’s work represents a new model of doing research. Usually, research findings take years longer to materialize than what most policymakers find useful. But his team is working fast and responding directly to what governments need, now. I hope more researchers take government partnerships seriously, and are flexible in adapting their research agendas to what real people need.

Which strangers might you give to?

My favorite charity of all time, GiveDirectly, has delivered over $50 million in cash transfers directly into the hands (really, mobile money accounts) of families living in extreme poverty since the start the pandemic.

I stan GiveDirectly so hard that I’ve convinced my friends who work in corporate jobs to use their matching program to donate to GiveDirectly each month. I ambush an unsuspecting dinner party stranger at least once a week with a conversation about my love for GiveDirectly. I give so much free PR to GD I should get a t-shirt, or something. Anyway, you should donate.