7. How reforming campaign finance can help fix democracy

And why politicians think their constituents are more conservative than they are

If you’re new here, please subscribe so you don’t miss the next issue!

Giving to Strangers is a newsletter for people who stare global problems in the face — climate change, animal welfare, global poverty — and believe that they require institutional, not just feel-good, solutions. Every week-ish, I share the ideas and people who are trying to make the world better, and offer a non-bogus thing that you can do to help.

Last week on Giving to Strangers, I dove into whether donating to campaigns actually helps candidates get elected. The conclusion was simple: donations matter more the smaller the campaign. Readers responded with a lot of thoughtful points, a few of which I want to share. (Name dropping ‘readers’ reminds me of those YouTube influencers: “Soo many of you guyss have requested a video about…”)

One of my friends ran for city council in Massachusetts, and wrote this about their campaign experience:

To reinforce the “it matters more the smaller you go” takeaway: my budget for my run for city council was $3000. My opponent spent $10,000. These are tiny amounts of money where another $200 means another precinct you can send direct mailers to. A good rule of thumb is that if the campaign / race is one that’s too small to have mass market television advertisements, then it’s one where your dollars are extremely valuable as they are paying for a couple salaries, mailers, FB ads, and like boxes of hand warmers for the volunteers.

My personal takeaway from “the smaller you go” principle is that we — people who do not hold elected office, nor have vast millions — have more power than we feel. And when RBG dies, or the West is in flames, local politics can be one of the most satisfying ways to throw yourself into something where you can make a difference. I’ll admit I haven’t been the best at this. But one way I’m trying to get more involved in my local Berkeley politics is by checking city council updates through the newspaper, Berkeleyside, which often digests council updates better than the city website. That’s how I found out about Berkeley’s redistricting, and applied to be on the city’s citizen redistricting committee. I’d urge you to subscribe to your most local newspaper.

Another response to the last G2S explains why (even well-funded) campaigns ask voters for donations:

People are loathe to change their minds or not show up on election day when they’ve already put money down. This is one of the reasons why a campaign will try to on ramp someone into being a donor by asking for $2 or other pittances; yes, a prior donor is your most likely future donor, but also a prior donor is your most likely voter.

So when you see a Joe Biden ad telling you that “even $2 matters”? Yeah. It matters for getting you to the polls.

This week: Citizen’s United and the rise of Super PACs

The research about advertising from last week is based on a candidate’s spending. Before 2010, spending by a candidate’s campaign and their party was all we’d have to worry about. But in 2010, the landmark Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission tilted the scales of political influence towards incredibly wealthy people and corporations. What exactly happened?

A January 2010 Supreme Court decision (Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission) permits corporations and unions to make political expenditures from their treasuries directly and through other organizations, as long as the spending — often in the form of TV ads — is done independently of any candidate. In many cases, the activity takes place without complete or immediate disclosure about who is funding it, preventing voters from understanding who is truly behind many political messages. — Open Secrets

That is, prior to Citizen’s United (followed by other Supreme Court cases such as McCutcheon v. FEC), if a wealthy donor wanted to support a candidate, their donation would be capped at $5,000. After Citizen’s United, “outside groups could accept unlimited contributions from both individual donors and corporations as long as they don’t give directly to candidates. Labeled ‘super PACs,’ these outside groups were still permitted to spend money on independently produced ads and on other communications that promote or attack specific candidates” (Brennan Center). So far in the 2020 election, Super PACs have spent over $1.2 billion, accounting for over 60% of all outside campaign spending, and 11% of total election spending.

But the independence between Super PACs and campaigns has turned out, in practice, to be a myth.

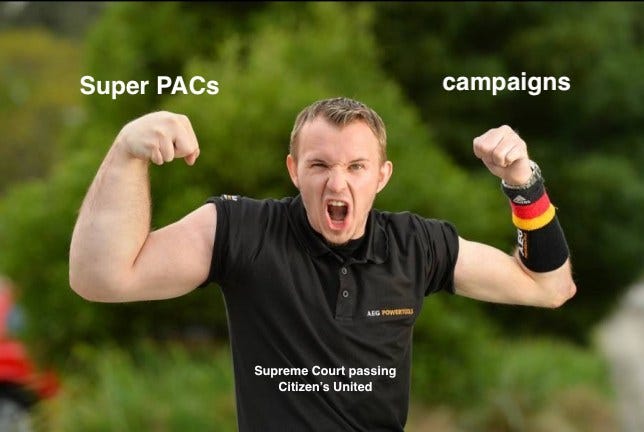

In fact, candidates’ favorite aides regularly get hired by super PACs for top jobs, signaling to big donors who’ve maxed out on individuals donations that the candidate “endorses” the super PACs, so the donor can just give to the super PAC instead. For maximum obviousness, candidates straight up attend super PAC fundraisers: Mitt Romney’s attendance at a super PAC fundraiser in 2012 was a controversial move at the time, but is now commonplace. In short, super PACs increasingly act as the incredibly well-funded and beefed-up “right arm” of the campaign, rather than innocent groups totally unaware of the campaign’s needs. So is there any surprise when the super PACs began expanding their role from airing TV ads, into activities that were once the domain of the campaign (including coordinating volunteers)?

^ Okay but really, thank you to Matthias Schlitte, German world champion arm wrestler, for lending your image to my analogy.

And we should care about who is giving money because it influences not just who is elected, but what politicians do once in office.

Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page, two political scientists at Princeton, studied whether US policy aligned more closely with the interests of business & wealthy donors, or with the interests of “average citizens and mass-based interests”. They compiled a dataset of polls conducted between 1981— 2002 that asked the public their opinion on thousands of different policy issues, and compared the public’s opinion to the number of powerful interest groups that had favored or opposed the issues. Then they looked at whether or not the policy was enacted within four years of the poll. They find that the opinions of average citizens and mass-based interests were not related to whether or not the policy was passed, whereas business and elite interests were. I don’t love this study for myriad reasons, but I include it as correlational evidence (and also because I already spent a while crafting this paragraph, so…sunk cost fallacy).

But more recently, Leah Stokes, a political scientist at UC Santa Barbara, published an award-winning study about how having close ties to interest groups shapes representatives’ views. Stokes and her coauthors surveyed senior staffers in Congress: people who closely determine the Congress’ policy agenda. Stokes found that senior staffers consistently get the opinions of their constituents wrong, believing that constituents are more conservative than they actually are. For example, Republican staffers thought that less than half of their constituents supported background checks for gun sales, even though the overwhelming majority (~90%) did. How much contact the staffer has with conservative interest groups in part explains this result: “Staffers who reported greater contact with corporate and ideologically conservative interest groups over liberal and mass-based citizen groups […] were less likely to get their constituents’ preferences right.” Wild.

A solution: public financing with matching

NYU’s Brennan Center released a report in 2018 detailing policy solutions to curb the outsized role that wealthy donors and corporations play in campaign financing. Their first solution? Establishing small donor public financing, without eliminating private funding, to amplify the impact that small individuals have on campaigns by matching their donations using public money.

It turns out this idea isn’t new. The report provides a brief history of public campaign financing, and I was shocked to learn how many presidents ran using public funds, and even more so that Obama was the first to say “fuck it” to the public financing system.

After Watergate, a robust presidential public financing system was enacted. From 1976 through 2004, most qualifying candidates participated. Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush all ran using public funds. But the system weakened, a result of inadequate funding levels and evasions through political party “soft money.” In 2008, Barack Obama made history by declining to take public funds; by 2012, no major party nominee joined the system. In 2016, former Maryland Governor Martin O’Malley was the only candidate to opt into the presidential public financing system.

New York City has already implemented public financing with matching. A New Yorker who donates $50 generates $350 for a campaign through a 1:6 matching program, as long as the donation is $175 or less. A candidate must opt into the program, and will receive public funds if they accept stricter disclosure limits and tighter individual caps.

And there are a number of other reasons why public financing of campaigns is a good idea. Just today the Brennan Center released a report detailing how public financing could help women and POC candidates, who have relied more on small donations in elections.

Which strangers should you give to?

I think a lot about the effectiveness of donating to address acute problems (deworming), versus donating to enact structural change (advocacy groups). This question drives me up the wall, because as much as I loathe to make ineffective donations, I also loathe to do nothing. Often, I try to aim for a sweet spot, where my donation can tip the scales on a person or intervention that will go on to have systemic impact (that’s why I was excited about being able to make a difference in close Senate races).

I’m featuring public campaign financing because it is precisely this kind of lynchpin policy that would enable a ton of other vital reforms. More than anything, it was Leah Stokes’ research on Congressional staffer perceptions that convinced me of this — if conservative business interests are the ones in front of staffers, staffers are going to start seeing their version of the world. And who is more likely to get that facetime? Big donors. So while supporting nonprofits who advocate for public financing is squarely in that unsatisfying, “long term advocacy and structural change” camp, the payoff to change is huge.

Donate here: Democracy 21 (led by Fred Wertheimer, the biggest advocate of public financing), Common Cause (which has passed several successful public financing measures).

If you found this post valuable or at least mildly apocalyptically entertaining, it would make my day if you shared Giving to Strangers with friends so they can subscribe: