17. A vaccine pep talk for liberals

In addition to being told that we're eligible, we should be made to feel good about it, too.

Welcome back to Giving to Strangers, a newsletter about how social change and how it happens, written by me, Anya Marchenko. The new quotes section is at the bottom. And if any of what I say below around vaccinate anxiety resonates, leave a comment below or reply to this email directly with your thoughts.

If you’re new here, welcome! And you can subscribe here:

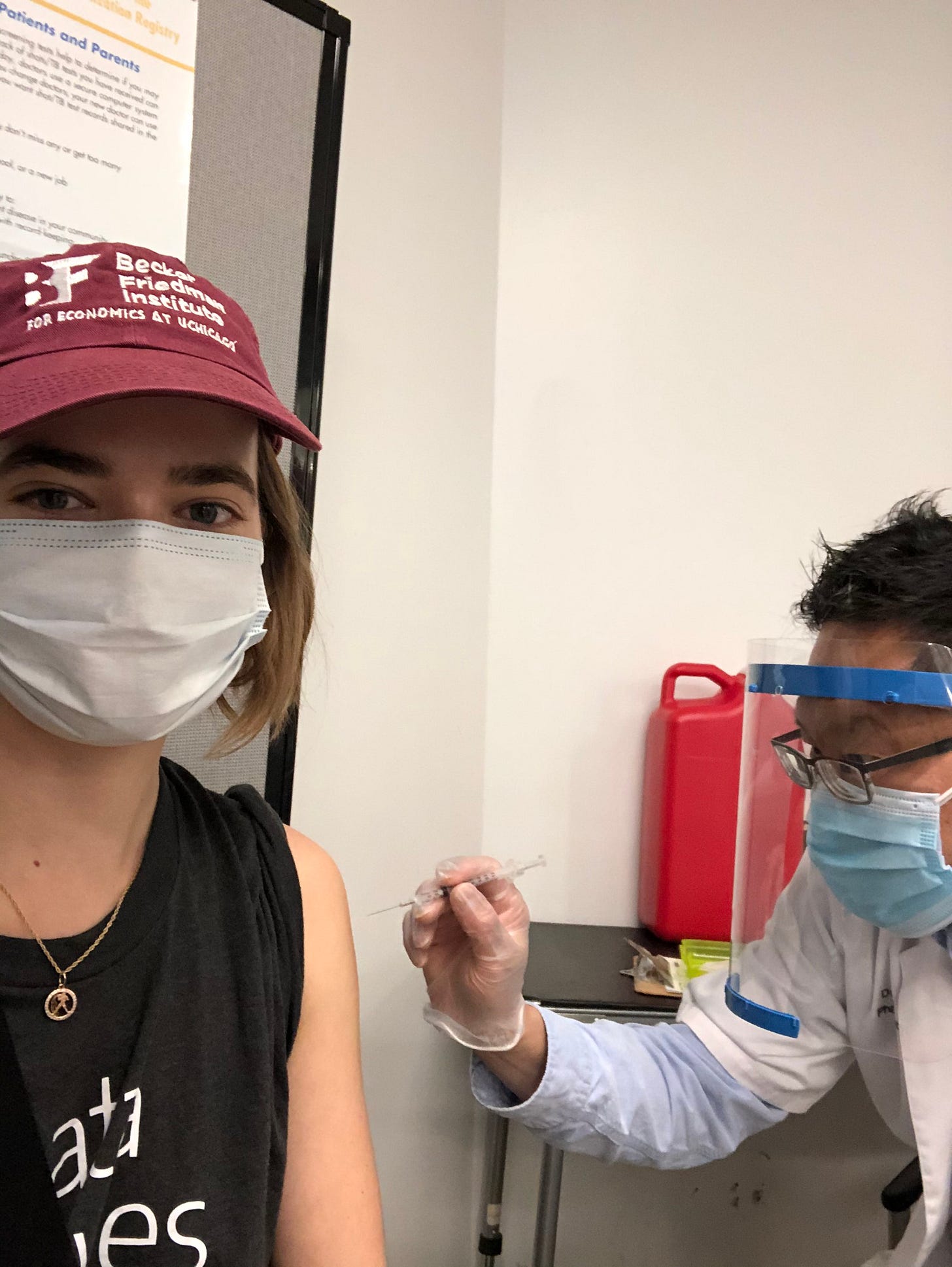

I got the COVID-19 vaccine last Friday. After receiving the email from UC Berkeley informing me that I was eligible as an “education” worker, I ignored it for a week. After all, I hadn’t been to the office since March and precisely zero youth rely on me for instruction, so the possibility that I could be truly eligible seemed too outlandish. Me getting it when people over 65 are still waiting their turn? No way.

Yes, way, it turned out. A coworker bumped the email, everybody in my office started signing up, and so it was that I got a slot at Walgreens.

At this point in the pandemic, in early March, being vaccinated against COVID-19 can feel more like winning the lottery than receiving medical treatment. Or like some sort of superpower you didn’t want to be in a position to have. I exercised my vax status for the first time on a run when an elderly couple suddenly stepped out behind a bush and into my path. Not wearing a mask, I veered jerkily off the sidewalk and yelled, “I’m sorry!” as a mea culpa for not wearing a mask, and then added, “Don’t worry, I’m vaccinated!” The couple waved amicably at me as I passed by: “Oh, no worries! So are we.”

Right now, many states are expanding vaccine eligibility past frontline medical workers and to people who may be less at risk, either because they’re working from home or have no preexisting conditions. And many of these newly eligible folks are questioning whether the vaccine is a privilege that they should have.

This tension is evident in last week’s question in the Ethicist column at the New York Times. A reader, who is eligible for the vaccine but is low risk and working from home, wrote in to ask whether it is ethical for them to get vaccinated when other people might need it more.

Kwame Anthony Appiah, who runs the column, responded:

I understand and respect your qualms. But you’re benefiting from a system that was decided on after considerable deliberation among democratically elected leaders and scientific experts. Because the priority list, though inevitably imperfect, is a legitimate one, you are perfectly entitled, as an ethical matter, to receive your vaccination. In doing so, you are contributing not just to your own well-being but to the health of the community, given the growing evidence that a vaccinated person poses fewer risks to others, and, finally, to the resilience of our medical system.

But it may be hard for people to really take this advice when the media has made vaccine desperation a topic du jour. I mean, just consider this excerpt from a NYT article about “vaccine lurkers” who drive around clinics hoping to get extra doses: “In Denver, suburban teachers stampeded a mass vaccination site after they got an email saying they had an hour to claim 200 unused doses. In Massachusetts, hourslong lines wrapped around a DoubleTree hotel after reports of extras ping-ponged across social media.”

If that’s what you think the world looks like, I can see why someone with a sensitive moral compass might start questioning whether they should really sign up now.

I’m not the only one who thinks these types of stories can create dangerous vaccine ambivalence. In an interview with Ezra Klein, professor and columnist Zeynep Tufekci criticized the media for being too conservative in its vaccine coverage:

To have [an amazing 95% effective vaccine] is wonderful. And it’s the kind of thing you would have national celebration and fireworks and church bells ringing and all of that. And then I spent the last couple of months reading a lot of doom and gloom about the vaccines, that I’m just like, I wake up every day, and I think this is amazing. This is so exciting.

And instead, we’re flooded with articles about, you can’t do this, you can’t do that. You can’t take off your mask. We don’t know if they prevent transmission. We don’t know this. We don’t know that. Which they’re not technically wrong, but to put the emphasis on some temporary limits and some temporary limits to our knowledge, rather than emphasizing how amazing they are….

My point is this: These types of articles can muddle the simple reality that eligible people have a moral obligation to get vaccinated, and that signing up is not only totally legitimate, but a citizenly thing to do.

Of course, you might respond: Well, if the rollout system is imperfect, and I’m low-risk, shouldn’t I wait to get vaccinated even if I’m eligible? Especially if someone higher-need can have the spot?

Sure. You could wait, and maybe someone will fill up that spot, or maybe they won’t. You could try to predict that by looking at your area’s vaccination rates, infection rates, or number of elderly people. You could talk to your friends who work in healthcare to get their opinion, and you could drive by the local CVS to see if there are lines. You could simply wait and see what your coworkers do. But while I understand the reason for this ambivalence — born out of a deep and genuine concern for one’s community members — it implies a behavior that doesn’t scale up to the community level. We can’t all just start guessing at whether it’s really “the right time” for us to get our shot. Coordinated responses work when communities align to follow a common plan made by experts, and the foundation of a collective plan cannot be so ad hoc. Sometimes, no matter how frustrating it is, the best thing to do is to obey an imperfect system.

That being said, it is absurd and maybe dangerous that lack of clarity means these kinds of cost/benefit calculations are left up to people in the first place. So in addition to making sure that people know when they should get a shot, local governments and employers should focus on making people feel good about doing so.

Reminders and PR campaigns are a good start: ideally, people should receive email or SMS as soon as they are eligible, which could also include encouraging messages around “doing your part,” even if you’re low risk. These texts can be sent through employers, which is often what sorts people into eligibility (i.e., I received my notification email as an employee of UC Berkeley, which received notice from the county that “education” workers were eligible).

Once people are vaccinated, we could take a few ideas from research in development economics to create positive framing around vaccines. In a (niche famous) paper, economist Anne Karing designed an experiment in Sierra Leone in which children receive differently colored bracelets for each necessary vaccine they got. She found that for certain vaccines (ones that parents already thought were beneficial), seeing children with bracelets increased the chances that other parents also vaccinate their kids. A lesson here is that social pressure, visibility, and maybe even a little positive recognition matter for vaccine take-up.

One way that this has been implemented is vaccine passports, which Biden has already asked his agencies to explore, and is something that Israel has already rolled out (though they’re not without concerns).

In short, local governments and the media need to do a better job of confidently and repeatedly encouraging eligible people to actually go get vaccinated. The media should realize that continuous vaccine desperation coverage could create feelings of scarcity that deter eligible people. And with more consistent, positive messaging, maybe vaccines would feel less like a perilous, precious resource available to the most vulnerable, but rather an important, and maybe even exciting, citizenly duty.

Have you had similar conversations with friends? Share this post:

Quodophilic Corner (Ha ha!)

As a quote lover, sharing some of the quotes I’ve written down over the last two weeks.

In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s there are few

― Shunryu Suzuki

When I feel confused about something, I write about it until I turn into the person who shows up on paper: a person who is plausibly trustworthy, intuitive and clear….Writing is either a way to shed my self-delusions or a way to develop them. — Jia Tolentino, Trick Mirror

The spotty acceptance of feminism has created a loophole for women in certain spheres, like media and publishing: claiming to have hurdled sexist obstacles where there were only other kinds of obstacle, we are able to take advantage of a feminist overcorrection. This is consistent with the trick-mirror-like quality of mainstream political and cultural discourse more broadly. The important question lying behind many possibly intractable issues is whether people are serious – whether their stated beliefs are authentic, or merely devised to achieve a certain self-presentation or outcome. Campaign polls, social media, ‘progressive’ politicians, ‘populist’ politicians, journalists invoking ‘free speech’ and ‘democracy’, quack doctors invoking science, your Facebook friends invoking quack doctors, skincare, astrology: clearly, not everything is what it seems, but it’s hard to tell what it actually is. — Lauren Oyler, London Review of Books

What does a too low social cost of carbon number mean? That we’re all going to fry if we use that number.

— Economist Joseph Stiglitz during a lecture on climate change

I had the same thought process in Hong Kong in the past few days, when all members of the Hong Kong University Faculty of Medicine, where I'm a researcher/teacher but not a doctor, became eligible for vaccination. I felt that front-line health workers need protection before I do, so I didn't sign up right away. But then the government opened eligibility to many occupations, including all teachers. I saw that the website wasn't swamped, and there were plenty of times available for vaccination, so I figured that I've done my part to allow more at-risk people a chance for vaccination, and I signed up for next week.

Compared to news stories from the US, where shots were hard to find, I'm shocked that vaccines are so readily available in Hong Kong, where COVID-19 has been much less common. There is some vaccine hesitancy here, with people waiting to see if other people here experience side effects after vaccination. It seems that many people don't trust news from other places. Also, statistics are poorly reported and understood. Some people were scared off by news reports that 3 people in Hong Kong died within days of being vaccinated, but news didn't report the number of deaths in a similar number of unvaccinated people as a comparison.

Super timely topic. I definitely had these qualms after reading this article about the inequitable vaccine rollout in Houston and Texas as a whole: https://kinder.rice.edu/urbanedge/2021/02/15/mapping-inequity-houston-covid-19-vaccine-rollout-pandemic-inequality.

The key paragraph: "In Texas, people who identify as Hispanic or Latino have suffered 43% of all COVID-19 cases, yet have received only 16% of vaccinations. Black Texans represent 19% of all cases but only 7% of all vaccine recipients, while Asian residents represent 9% of all cases but only 1% of vaccine recipients." :'(