Welcome back to Giving to Strangers, a newsletter about how social change and how it happens, written by me, Anya Marchenko. You can follow me on my newfangled Twitter.

And if you’ve made it here (welcome!) but you’re not subscribed yet, let me help you with that:

We are in a moment when companies in energy, animal agriculture, and other traditionally exploitative industries are at a crossroads: carry on as usual, or transition to less harmful business practices. BP and Shell have already started renewable energy projects. Companies that slaughter animals are now producing plant-based meat: Tyson, the biggest food company in America and the second largest meat producer in the world, appointed a head of alternative protein, proclaiming they are now a “protein leader” (“We are more than chicken”).

The biggest question is whether or not these changes are inevitable. In other words, are companies transitioning because they see the writing on the wall, and new technology and shifting consumer preferences have made the “humane” option simply more profitable? Or is diversification just greenwashing, allowing companies to maintaining a stubborn grip on business practices that pollute, kill, and extract, but now with less criticism?

This fragile teeter-totter is particularly sensitive to legislative, economic, and activist forces that could push it definitively over to one side or another. But consumers often don’t see the forces that shape what products they’re able to buy. Grocery store pledges to “source ethically” likely belie three years of negotiations by dogged activists that pushed the grocery chain in that direction, and your oat milk brand likely had to fight hard to even be sold in the milk aisle. And sometimes, those forces are just ordinary people who’ve made it their mission to change something about our food system. Josh Balk is one such hidden force.

The man behind your cage free eggs

All I do is wake up in the morning and work to abolish cages. That is what I'm doing. That is it. I am single-focused. I am relentless, obsessed, and rarely other thoughts ever enter my mind when it comes to animals other than ‘How do I abolish these cages forever?’

If you’ve ordered an egg McMuffin at McDonald’s, shopped at Costco, or eaten at a school or college cafeteria, it is likely that Josh Balk had a hand in the cage free eggs you purchased or plant-based burgers you enjoyed.

As the Vice President of Farmed Animal Protection at the Humane Society of the United States, Balk’s job is to convince companies to start using cage free eggs, put plant-based foods first, and lobby state legislatures to pass stricter animal welfare protections. But Balk is innovative beyond his job description in his advocacy for animals. He’s also the co-founder of JUST foods, a startup that makes that eggless eggs you see on supermarket shelves, and the co-producer of Netflix’s 2018 documentary Game Changers.

Giving to Strangers spoke with Josh Balk to understand what strategies he uses to convince corporations to change their behavior, whether cage free actually matters for hen welfare, where we stand in the fight to end confinement.

Humane Society has been on the forefront of cage free egg advocacy for at least 10 years

The Humane Society is the force behind a lot of this nation’s progress towards cage free conditions for chickens. They have already gotten nearly every major food company in the country — restaurant chains, grocery stores, food service companies, food manufacturers — to commit to cage-free eggs. But of course, none of this matters unless companies actually sign contracts to change supply chains. So the Humane Society has also released an industry scorecard to understand whether the companies who’ve already pledged are actually meeting their commitments. It is also a “form of spotlight”, says Balk, to let companies know they’re being watched.

The Humane Society also spearheaded bans on extreme confinement in a dozen or so state legislatures. Balk was behind the monumental passing of California’s Proposition 12, widely regarded as the strongest law in the world for farmed animals. Passed in 2018, it not only abolishes extreme confinement of certain farm animals raised in California, but goes one step further to prohibit all sale of meat and egg products from extremely confined animals. This means that not only are Californian egg producers prohibited from keeping eight chickens in a space the size of a microwave, but farmers in any other state who want to sell chickens in California cannot do so, either.

The result of these and other campaigns is that 30% of chickens are now cage free in the United States, up from the single digits a few years ago. And according to USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service, by 2026, approximately 64% of U.S. hens must be cage-free to meet projected demand. Now, “90 million animals will never know what it’s like to be confined in a cage, per year,” says Balk. “That might be the greatest reduction of farm animal suffering in the history of the United States.”

Let’s take a step back to understand why these changes matter?

Does cage free matter?

In short, yes. A lot.

As a consumer, I understand skepticism of whether the cage free label (as well as pasture raised and free range) actually represent better animal welfare conditions. The New York Times summed up this tension nicely in a 2016 article headlined, “Eggs That Clear the Cages, but Maybe Not the Conscience”. Make no mistake — nobody believes that cage-free conditions are utopian or even ethical for chickens. But the cage free standard nonetheless really matters.

Here’s how Balk describes it:

Getting [chickens] out of cages vastly improves their animal welfare, far greater than getting animals who are cage-free to outdoors, far greater than animals who have outdoors to turn organic, far greater than animals who are organic and to go pasture raised. It is a massive difference between being a chicken in a cage the size of a your home microwave with eight other chickens — and that's every single moment of your life: where you stand, where you sleep, where you eat, where you defecate, where you lay your egg…that is the same spot every single day for a year and a half — comparing that to living cage-free.

Like if they could talk, they'd be like “Anya really? Like, you're worried about my chicken cousin who already is out of a cage and running around outside, but maybe doesn't have pasture? Well, guess what? I can't move my wing, ever. How do you like that?”

So we focus to get these birds out of cages, versus trying to focus on the tiny percent of birds who already have outdoor access to have even more outdoor access.

So those are the wins and why they matter. But how do you get there?

“Just do the right thing"? Nah. Exposure to risk and liability, legal consequences, push companies towards ethics

It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it. — Upton Sinclair

I asked Balk to paint a picture of what it’s like in the proverbial boardroom when he comes to talk to food companies about animal welfare. What kinds of arguments does he make to convince conglomerates to change something they’d prefer to ignore? Do companies see him as a nuisance, or a potential resource to help them reform in ways they already know they need to?

Balk says that in most (not all) cases, “food companies do not want to deal with issues related […] directly to ethics,” while quickly clarifying that he doesn’t think “that people working there are bad people at all,” and that “these are very busy people who, at their heart, care about making the world better.”

Unlike many radical activist groups who are not invested in corporations thinking nice of them, Balk’s work toes a fine line between wanting to keep companies receptive, while still pushing them to change.

When we make the case why companies should go cage-free, it certainly is helpful to say that this practice is criminal animal cruelty in many states. And all of a sudden, it's not so easy to think, ‘Oh, this is some fringe issue some people care about.’ No, this is animal cruelty. These practices are animal cruelty by the letter of the law in numerous states where you operate, where you sell your products, where you have staff.

Balk is referring to the laws passed by California, Oregon, Washington, Massachusetts, Michigan and Colorado that prohibit both the sale and production of cage eggs. Several other states have varying levels of restrictions — Ohio bans new construction of battery cages, and Rhode Island bans all cages for hens but not the sale of eggs from caged hens.

The discontinuities that different regulations create can be a useful lever when convincing companies. Balk sometimes reasons to them that “instead of having a supply chain where some of your supply chain is utilizing a practice that is legal, and another part is utilizing a practice that will be criminal animal cruelty, why don't you just keep one supply chain that doesn't have to worry about parts being involved in criminal animal cruelty?” This is a helpful argument that leverages legal and business considerations, instead of “pleading with companies to do the right thing”, says Balk.

And that’s because the way that Balk tells it, when the Humane Society talks to employees in Big Food, animal welfare “is just another thing for them to worry about” amidst their routine workplace problems like broken supply trucks and mislabeled products. The image of executives and managers hearing a presentation about gross animal rights violations in their company with the same “this job, amirite?” sigh as a broken truck boggles my mind.

Balk sums it up nicely:

What I found is this is that mostly people who work at food companies are not there to torture animals. Most people who work at food companies went to business school. They're interested in corporate structures and building businesses and growing businesses and making money for their family to have a home, send their kid to college, maybe go on vacation. These are ordinary values that people have.

At the same time, I believe that in most cases, corporations don't care enough to alone do the right thing.

What is the meat company of the future?

Balk is enthusiastic, charismatic, the kind of person you’d expect to be convincing across the table. But he is also staunchly pragmatic, having no illusions about abolishing animal agriculture, or appealing to people’s better angels to get them to change (“we win not by begging people to do the right thing”).

So that’s why it was that much more surprising when he said he’d be “surprised if there are major meat companies that aren't only selling cultivated and plant-based meat 25 years from now.”

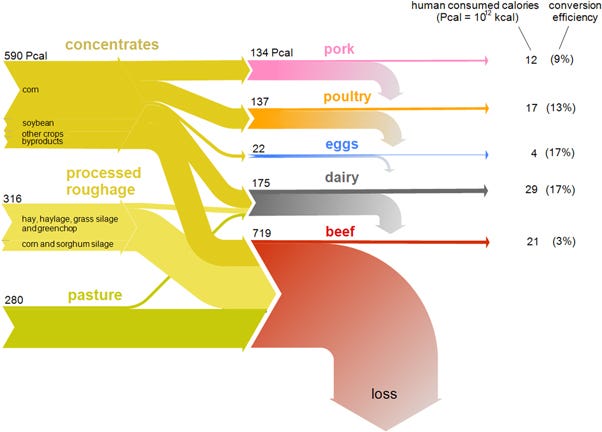

Balk cites the inefficiency of feeding plants to animals to make protein, rather than making protein directly, either through lab-grown meat or plant proteins. By feeding beans and wheats to chickens, pigs, and cows, we are essentially transforming plant calories into meat calories. But most of those calories — between 80% and 97% — are ‘lost’ along the way to other processes the animal needs to live.

Balk:

Plant-based is going to catch up. And I believe in twenty-five years, cultivated meat is going to get to the point where it is as affordable as meat from animals who were killed.

In 25 years, does it mean that Tyson and Smithfield and Perdue and all of them are out of business? No, I don't necessarily think that. I think that they've evolved to sell - as they would say - “protein”, but just different types of protein, from different sources.

A practical blueprint for change

At least in the animal welfare space, corporations aren’t welcoming activists with open arms. Hell, sometimes (extrapolating from Balk’s descriptions) corporations don’t even have a good understanding of what their business practices look like — horrible animal conditions in slaughterhouses is surprising news to some people working for meat companies. How could they be amenable to change if they don’t even know what needs to be changed?

So making corporations more ethical doesn’t happen by appealing to ethics. But maybe it happens by exposing liabilities (or potential future liabilities), and arguing that the more humane way is actually the more efficient way.

Saying ‘watch out, you are or might soon be doing something criminal’ could be effective if statutes exist, but there is a dearth of statutes in animal welfare. This highlights the importance of passing legislation, as even state laws can send ripples through supply chains, in addition to serving as leverage for activists to use in future lobbying. Consumers have a lot of power over their state animal welfare laws — animal welfare propositions tend to be incredibly popular if they’re put in front of voters. So make sure to pay attention to efforts to put animal welfare on your state ballot.

Which strangers should you give to?

If you’ve read all the way here, you’ve seen how effective the Humane Society has been at creating real change for animals. Since advocacy is hard to track (unlike delivering medicine or goods or cash), I feel personally comfortable trusting the track record of the Humane Society. However, a consideration I haven’t touched on is tractability, or whether the Humane Society could effectively use your extra dollars. This is something you might want to look into if you have more questions about donating for animal welfare.

You can donate here:

Awesome